Of all the criticisms lobbed at Washington senior Jake Browning in the midst of this QB controversy that the Internet has spoke into existence, the most pervasive is the idea that while Browning’s play might be good enough for the Huskies to dominate lesser conference foes, he’s not good enough to win “the big one.”

Washington has in fact gone 0-3 so far in non-conference games against top-10 foes during Browning’s career, losing the CFP semifinal to Alabama in 2016, last year’s Fiesta Bowl to Penn State and this year’s season opener against Auburn. But do those outcomes reflect Browning’s play? And does he actually struggle the better the opposition, at least more than the typical quarterback?

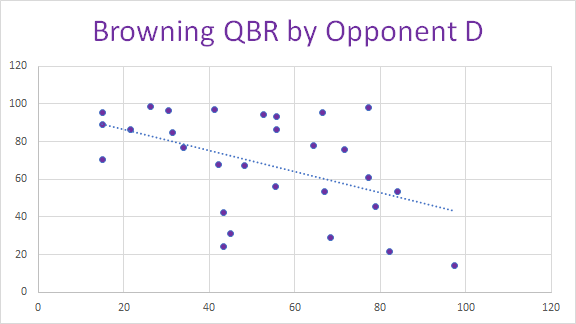

Let’s start by taking a look at Browning’s QBR (an ESPN rating that incorporates both passing and running, making it a far better capture of QB performance than the outdated passing-only rating used by the NCAA) by opponent team defense as ranked by ESPN’s Football Power Index efficiency.

(One technical note: Since FCS opponents aren’t included by FPI, I assigned them a defensive rating of 15, typical of the worst five defenses in FBS.)

As the critics suggest, Browning has in fact been less effective the better the opposition gets, as indicated by the best-fit trendline sloping downwards. He’s tended to dominate the lesser competition the Huskies face in non-conference play, while his two very worst performances by QBR have come against two of the three best defenses Washington has faced (Alabama, naturally, and also the 2016 Colorado Buffaloes team the Huskies beat in the Pac-12 championship despite Browning completing just nine of 24 attempts).

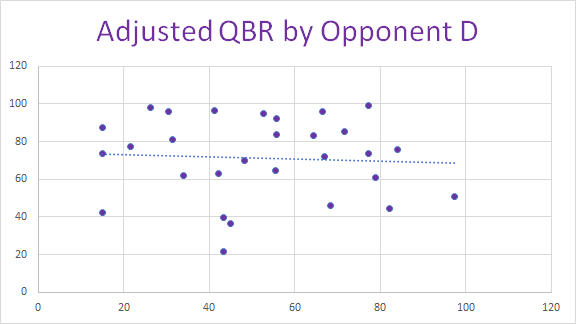

Ah, but this is raw QBR. What about when we adjust for opponent quality using adjusted QBR?

All of a sudden, the downward slope of the best-fit line all but disappears. Yes, Browning was uncharacteristically poor against Alabama and Colorado, but his adjusted QBR in Washington’s other neutral-site losses (73.7 vs. Penn State, 75.6 vs. Alabama) was actually better than his overall average.

In fact, Browning’s average adjusted QBR against the seven defenses he’s faced with an FPI efficiency of better than 70 (69.6) is higher than his weighted average against defenses with a rating of worse than 50 (67.0) — the continued negative trendline owes only to how dominant Browning has been against middle-tier defenses the likes of which the Huskies typically face in conference play (78.2).

So why does it feel like Browning struggles in big games? I think there are three factors. First, while this kind of adjustment is easy to make for weak opposition because those games feel less meaningful and important, it’s probably harder for us to mentally adjust for how good elite opponents are.

Second, the definition of what qualifies as a “big game” is somewhat arbitrary. Because Washington won those games and went on to play bigger ones, Pac-12 games don’t get counted for better (Browning’s Pac-12 championship struggles are rarely held against him) or worse (Browning doesn’t get credit for torching a 2016 Stanford defense rated the same as Penn State for 10.0 yards per attempt and 71 percent completions).

Most of all, though, it feels like Browning struggled precisely because the Huskies lost those games, making it easy to see how a better performance could have translated into a different result. Less of the criticism has gone to the UW defense that allowed Penn State to convert 13 of 17 third downs and Auburn nine of 18.

So yes, Browning hasn’t been as effective in big games, but only because nobody is as good against better competition as weaker competition — something that’s applied to the Huskies as a whole in their losses, not just their oft-maligned quarterback.